Ulam numbers

The Ulam numbers are defined to be the positive integers that can be written as the sum of two distinct smaller Ulam numbers in exactly one way, with 1 and 2 as base cases. The first few Ulam numbers are:

1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 11, 13, 16, 18, 26, 28, 36, 38, 47, 48, ...

One of the most fundamental questions we can ask about the Ulam numbers is

“What is the limiting density of the Ulam numbers?”

In other words, if u(n) is the number of Ulam numbers below n,

what is u(n)/n as n grows large?

The first person to take a guess at this question was Stanislaw Ulam himself,

who conjectured the density of Ulam numbers is 0.

This kind of makes sense:

Given cn integers randomly distributed in [0, n),

then there would be about c2n ways to write n as the sum of

two of those integers, and so a linear density would not be maintainable.

However, the reality is very different.

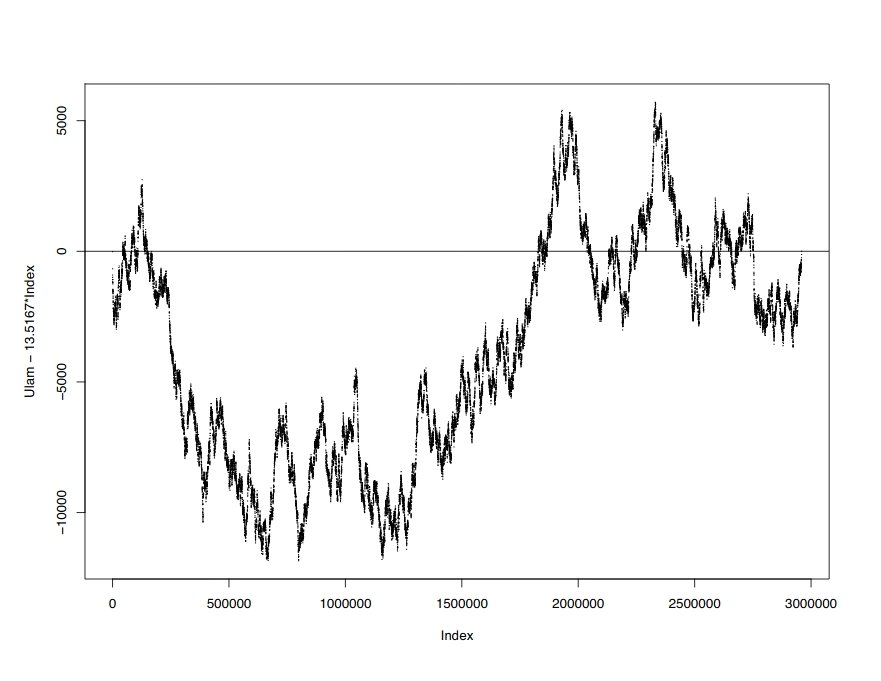

The ith Ulam number trends towards 13.5167i as i gets large.

In other words, the true density is about 1/13.5167 ~ 0.0739879.

Here’s a plot showing this behavior up to the 3 millionth Ulam number:

Why does this happen? While this is an open problem, we can get a bit of intuition by looking at a sequence I’ll call the “Ulam-0” numbers, which are the positive integers that can be written as the sum of two distinct smaller Ulam numbers in exactly zero ways, with 1 and 2 as base cases. The first few “Ulam-0” numbers are:

1, 2, 4, 7, 10, 13, 16, 19, ...

The “Ulam-0” numbers are the numbers which are 1 mod 3, and also the number 2.

The long-term density is therefore 1/3.

This is true despite the fact that the “cn” argument above applies

to the Ulam-0 numbers just as much as it applies

to the Ulam numbers.

So is there a modulus hiding in the Ulam numbers?

The answer, surprisingly enough, is yes.

The best research on this has been conducted in the (pre-print) paper

The Ulam Numbers up to One Trillion

by Philip Gibbs and Judson McCranie.

The hidden modulus is 2.443442967784743433...,

which the authors call 𝜆.

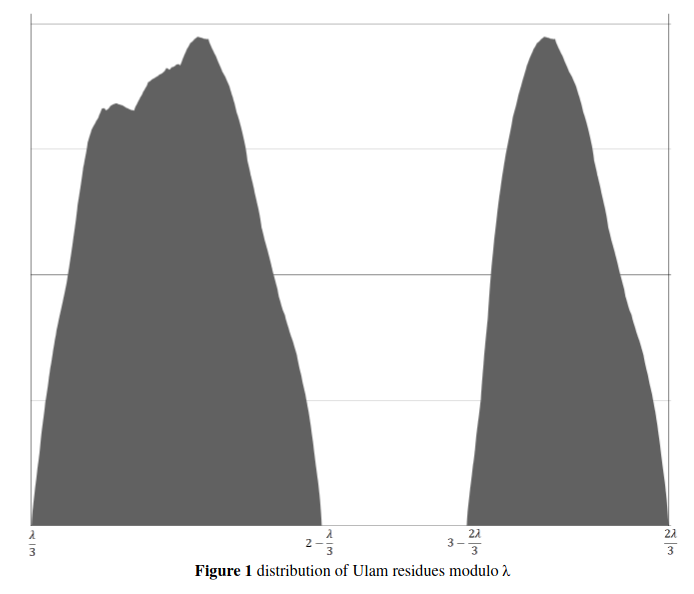

Once we have this modulus, we can find that almost all Ulam numbers lie

between 𝜆/3 and 2𝜆/3 modulo 𝜆.

Here’s a probability distribution of the first trillion Ulam numbers

modulo 𝜆:

Outside that middle third there are almost no Ulam numbers:

there are only 6495 outliers among the first trillion Ulam numbers.

Despite how rare these outliers are,

the outliers are incredibly important.

The sum of two numbers in the interval (𝜆/3, 2𝜆/3)

will always be outside that interval,

so almost all Ulam numbers are the sum of one number in the interval and one outlier.

Now, finally, we understand why the Ulam numbers can have a nonzero density: The linear amount of numbers in the central third is balanced by the tiny amount of outliers, resulting an appreciable fraction of numbers continuing to be Ulam numbers.

Now that we understand why a nonzero fraction of numbers are Ulam numbers, the open problem remains: Can we prove it?